How to Create Slow Streets During the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended daily life across California. In an effort to enforce physical distancing, many local and state parks have been closed. Yet, people need to get fresh air and they need to exercise. During the stay at home order, many more people than usual are walking, running, or biking. Advocates have been pushing local governments to create Slow Streets – streets that prioritize human movement and provide the space people need to exercise and still stay safe.

Adversity is a great teacher. It shows us what we need more clearly than words can explain.

Like the Open Streets movement, these hyper-local Slow Streets give residents a chance to experience their neighborhoods in a new way. Without cars, streets are wide expanses available for rolling and playing. Kids can learn to bike without worrying about traffic.

Cities around the world and across the US have reallocated street space for use by people-powered movement during the shutdown. California cities, however, have been slow to join the movement. Oakland was the first California city to create Slow Streets for recreation, starting on April 14. As of this writing, Oakland has been joined by neighboring Emeryville and San Francisco. Advocates in Los Angeles, San Diego, Berkeley, Alameda, and other cities are pushing their local governments to follow suit.

If you want to bring open streets to your community during California’s stay at home order (or anytime), here are some tips on how to make that happen.

A Guide to Bringing Slow Streets to Your Community

To compile this guide, we spoke with some of the activists who helped pioneer Oakland’s Slow Streets. Advocates from Bike East Bay, Walk Oakland Bike Oakland (WOBO), Transport Oakland, and TransForm worked with the city to help launch an ambitious project to create 74 miles of temporary open streets, called Oakland Slow Streets.

While every community has different concerns and considerations, the takeaways from Oakland’s launch are a good place to start. The city established an important principle up front, by committing not to use the Slow Streets program as an excuse to hand out traffic tickets. In addition, Oakland’s diverse neighborhoods and residents provide lessons that will be applicable in many California communities.

It helps to have a strong advocacy community

When the shelter in place took effect in the Bay Area, advocates got together to discuss the changes needed to keep people safe on the streets. They presented a list to OakDOT. The list included turning off beg buttons, widening sidewalks with cones, changing traffic lights to flashing lights, and messaging about safe driving.

Oakland’s DOT was reluctant to implement most of the items on this list (the advocates are still working on this). But the department surprised them with a different, bold option: a plan to open 74 miles for human-powered recreation. While the city advanced this plan, participation and support from advocates was essential and they continue to work with the city on implementation and iteration of the program.

It’s not too late to bring Slow Streets to your community. Find your local bicycle coalition or active transportation group, join, and agitate!

Build relationships with city staffers and elected officials

The long-term relationships between advocates and city staffers created a foundation of trust. That made it easier for Oakland to launch its ambitious program, because it knew it could lean on walking and biking nonprofits to supplement city resources. And the solid relationships meant that it was easy for each party to reach out to the other.

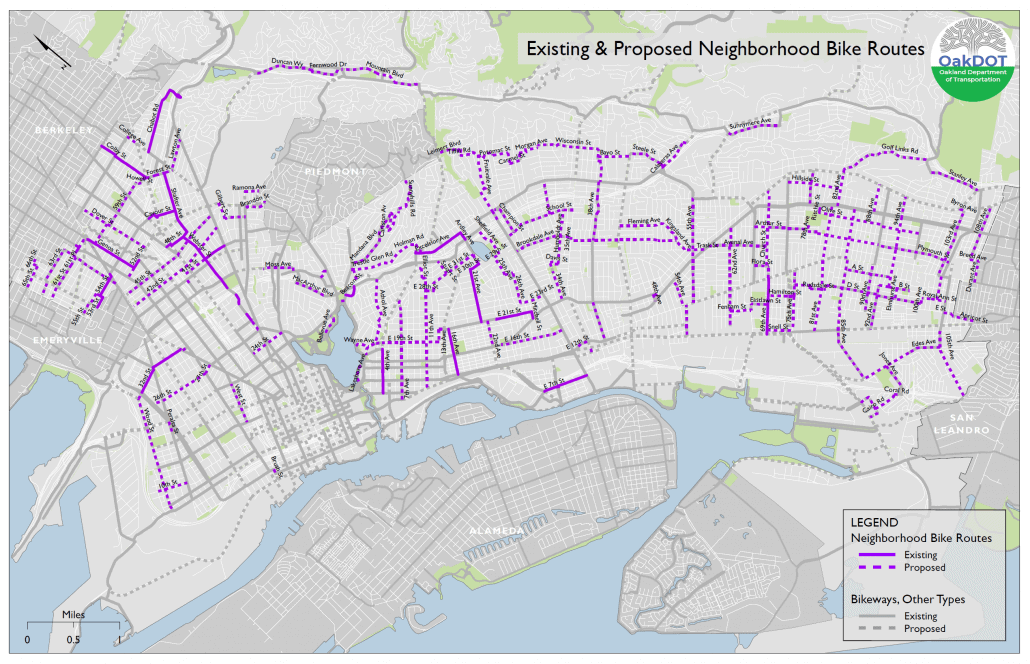

Build on existing bike networks and campaigns

Oakland chose the 74 miles of current and planned neighborhood bikeways to designate as Slow Streets. While some streets have been taken off the list and others added, the fact that these streets were already in the bike plan gave the city a starting point for the Slow Streets program. Campbell said that the fact that the streets were already in an approved bike plan helped get the city council members on board with Slow Streets.

In addition, speeding was an issue in Oakland neighborhoods long before the stay at home order. “This is such a quick implementation, but WOBO had been pushing the Slow Oakland campaign for many months in advance,” said Chris Hwang, the president of WOBO’s Board of Directors. WOBO was already working on a Slow Oakland campaign to raise awareness of the impact of speed on survivability, street design to lower speeds, especially around schools, and getting people to take a pledge to drive more slowly.

That campaign provided a ready-made foundation for Oakland’s Slow Streets. “It’s not a coincidence that the new signage that’s going up looks like our Slow Oakland materials,” Hwang said.

Keep up the pressure

Oakland is an unusual case because city staffers came up with their own bold plan and had the willingness to roll it out quickly. “Our wish list did not include 74 miles of Slow Streets,” said Bike East Bay Advocacy Director Dave Campbell.

In this case, the city exceeded the advocates’ expectations. But, without a strong advocacy community to lobby for the needs of bicyclists and pedestrians, the building blocks for the city’s plan might not have been in place.

And, in many other cities around California, it’s pressure from bicycle and pedestrian advocacy organizations and others that will convince staffers and elected leaders to create Slow Streets. It doesn’t hurt that Oakland did it first to provide an example. But activists applying pressure is a key element. Don’t give up.

Do as much outreach as possible and engage local residents

Outreach is hard when you are implementing a quick solution during a crisis, but it’s still essential. “To build a really strong community, you’ve got to have people feel welcomed and that they can be engaged and things don’t have to be dumbed down for them. People are very smart about what needs to be done for their community,” Hwang said. “We tend to be a little bit blind to what people hold closely as priorities for themselves and their families. We could do way better on that.”

However, as Campbell noted, “You can’t knock on people’s doors” because of physical distancing rules. In Oakland, supporters turned to social media as one way to spread the word. “You need engagement because someone is likely to complain,” he noted. You need a local resident to say, ‘This is more important than your concern.’”

In Oakland’s case, much of the outreach has been done during the project. Oakland started with just four streets and has added a few more each week, making adjustments based on community feedback. San Francisco seems to be following a similar model with its COVID open streets program.

Choose your branding carefully

Oakland set a good example with its Slow Streets program. CalBike has been hearing from our statewide network that Slow Streets is a better way to brand these temporary open streets than names that include Open Streets or Safe Streets. A name like Slow Streets helps politicians understand that the streets aren’t closed to cars completely, only to faster through traffic. This helps allay concerns that these streets for COVID distancing will be similar to Open Streets events, which can draw large crowds.

“I think Slow Streets work better for Oakland,” Hwang said. “It differentiates from Open Streets events, and is a bit more descriptive for neighbors and drivers alike.”

Even better, Slow Streets is a concept that can extend to a permanent network of greenways for safe and low-stress biking. Oakland’s Slow Streets, after all, were built on the foundation of WOBO’s pre-coronavirus campaign to slow traffic and create safer streets. If you call your plan Slow Streets (or something in that vein), you are well-positioned to lobby to make all or part of the program permanent after the pandemic passes.

Create a mechanism for evaluation and feedback

It’s important to give people an easily-accessible way to provide feedback (other than knocking over barricades). In Oakland, that has taken the form of a survey and calls and reports to 311.

It’s important to see how people are using the open streets and whether they relieve pressure on crowded parks. This is something that advocates can help with. “In Oakland, we’re ready to do almost all of the evaluation,” Campbell said.

Be willing to iterate and save some resources for adjustments

Ben Kaufman of Transport Oakland, said, “In some neighborhoods there’s a huge response. In others, there’s not much change in the streets. Be able to iterate if you need it.”

Iterations require budget. Make sure the city reserves some budget to implement changes.

Leverage existing networks to get the word out

“You don’t have to build up neighborhood networks from the ground up,” Hwang said. They are already there and you should use them to get the word out so local residents feel included in the process. This can include neighborhood associations, churches, health clinics, and school districts. The Oakland Unified School District does mass communication to thousands of families and distributes food at several locations. Hwang suggests getting “trusted messengers” to spread the word as much as possible.

Keep it simple to minimize staff time needed

One objection that cities have raised to COVID open streets is that they don’t have the budget to implement it properly. However, these projects can be simple and cheap. In Oakland’s case, the city kept things low-key, with barricades and signage to mark the Slow Streets. Neighboring Emeryville brought in water-filled barriers to separate people from cars.

The city will need some engineering time to draw up plans for traffic diversion and crews to place barricades and signs. Bike coalitions can help by asking volunteers to put up signage and serve as (safely distanced) ambassadors. Getting local residents to act as block monitors also helps. “They can be the best messengers of what this is about,” Hwang said.

Oakland may not be able to get to all 74 miles of streets in its plan. “I think it reflects the very real resource constraints the DOT is under,” Kaufman said. He noted that, if the city’s DOT were fully staffed, it could have implemented the plan more quickly.

Still, if Oakland can find a way to do COVID open streets while short-staffed, other cities have no excuse.

Recognize that different neighborhoods may need different solutions

Hwang noted that neighborhoods where there were Oaklavias (Oakland’s Open Streets) tended to embrace the Slow Streets. “Having a real life experience with what things could be like made them more receptive,” she said. “I worry that it’s an uneven experience. You shouldn’t expect that people are going to take this up right away.”

Allow neighborhoods to give their open street its own flavor. Rather than a one-size-fits-all model, create a big framework that can encompass different manifestations.

Support DIY street closures and help make them official

Some people in Oakland couldn’t wait for Slow Streets to come to them, so they made their own. In Oakland’s Brookdale neighborhood, residents closed the street completely using art and found objects and providing their own block monitors. The DIY element adds creativity and fun to open streets.

“That’s a good example of neighbors DIY upgrading a Slow Street and making it better,” Campbell said. “A successful program has a significant DIY component to it.”

Keep Slow Streets local

Slow Streets are different from Open Streets events. You don’t want people to come from all over the city to enjoy the open streets because that can create crowding, which is exactly what COVID open streets are designed to remedy.

You want residents to know it’s coming and to know what it is when it shows up. But you don’t want to tell people who live far away too much because then they’re going to go to it. That’s the challenge,” Campbell said. To keep the streets open for local residents, he said, “Do more than one street. Do a lot.” That’s the best way to create enough space for safe local recreation.

Good signage is a vital communication tool – and it’s harder than you think

Oakland’s Slow Streets allow access for local car traffic, deliveries, and emergency vehicles. Their signage said, “Road Closed to Thru Traffic.” Many people misinterpreted or misunderstood this wording.

“A lot of people did not understand what ‘no thru traffic’ means,” Hwang said. In addition, it was tough to translate that wording into other languages. For example, the concept of “thru traffic” doesn’t directly translate into Chinese. What we think of as simple road signage is not so simple,” she said. “Even in English, people didn’t understand.”

Kaufman thought more nuanced signage would have helped in the initial rollout. “It took us a couple of weeks for the city to have signs people could print out,” he said. He felt that signage with the Slow Streets branding made it easier to communicate to local residents.

Don’t use the police to enforce the open streets

One of the big concerns in Oakland is that Slow Streets might bring oppressive enforcement into communities that are already over-policed. It’s a program failure if open streets lead to racial profiling or oppression of disadvantaged communities. “You just don’t want the police involved,” Campbell said. “You want them doing things that are more important for police officers to do.”

“There should be no need for the police,” he added. “If the design of your system requires some kind of enforcement or security personnel monitoring, you didn’t design it right. Go back and redesign it.”

Toole Design has additional insights about not using police to enforce social distancing and open streets.

More resources for creating #COVID19Streets

There are some great resources for planners and advocates who want to create Slow Streets.

Toole Design recorded a webinar about Rebalancing Streets for People.

The League of American Bicyclists hosted a webinar on adapting streets for COVID-19.

The Rails to Trails Conservancy also held a webinar and you can watch the recording.

NACTO has created a toolkit of rapid responses for cities.

If you need more inspiration, urban planner Mike Lydon has been tracking #COVID19Streets from around the world in a google spreadsheet, to give you a basis for comparison. Transportation researcher Dr. Tabitha Coombs has compiled a comprehensive database of urban responses to the need for more open space around the world.

Oakland’s experience covers a lot of bases, but other communities may have additional issues. Did we miss something that’s important in your neighborhood? Is there a resource we didn’t include? Let us know. We will update this guide with additional best practices.